The most radical economic concept or theory I have ever read is set out in Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s book, What is Property? Before explaining why I consider it to be so radical, I need to explore the concept of property in more depth.

Property is the legal right that a person has to use, enjoy, dispose of, and claim an asset, whether movable or immovable. In this article, I will focus only on immovable property.

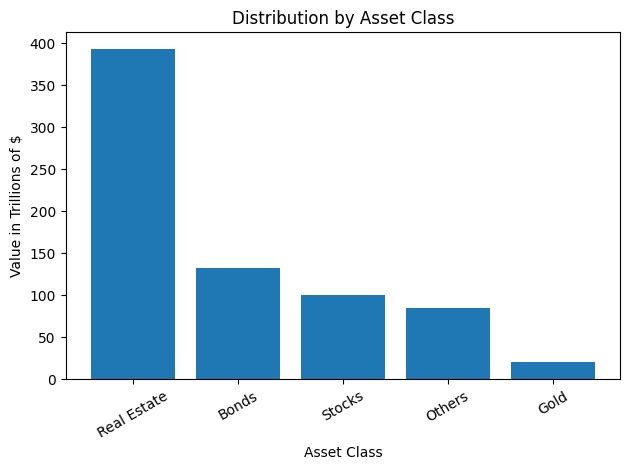

The global real estate market, including housing, is by far the largest asset class, valued at approximately $393.3 trillion at the beginning of 2025.

In the article I wrote about crime, I stated that all crimes constitute a violation of property rights. The right to freedom of expression is a right to ownership of our voice. The right to life is based on the right to our body or self-ownership. The right to private property is the natural extension of these rights to acquired material goods. Or is it?

In his book, Proudhon states that “property is theft!”. For the author, the fragility of the concept of property lies in the fact that it can only be validated by recognition and registration by the state. While legal property requires formal titles, a man who clears his land, cultivates it, builds his house, and derives his livelihood from it holds possession based on three grounds:

- As the original occupant;

- As a worker (as a result of their labor);

- By virtue of a social contract (or mutual recognition between peers).

According to Proudhon, permanent property is a concept created by civil law. In establishing this notion, the law did not base itself on the development of a natural law, nor did it apply a moral principle; it literally created a right outside its jurisdiction. It sanctioned selfishness.

Agriculture was the foundation of land ownership and the original cause of property. What was the point of guaranteeing farmers the fruits of their labor if the means of production were not simultaneously guaranteed, such as land, tools, and a place to store them?

Every individual has an equal right to occupy land. By what right did man appropriate wealth that he did not create and that nature gave him freely?

“GOD GAVE THE EARTH TO THE HUMAN RACE: why then have I received none? HE HAS PUT ALL THINGS UNDER MY FEET,—and I have not where to lay my head!” — Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Light, water, and the air we breathe are elements that cannot be appropriated, as they are infinite natural resources. Land is a finite resource with properties that make it suitable for commercialization. However, for this very reason, should it be subject to private ownership or, on the contrary, a common good accessible only through possession and enjoyment?

Just as fishermen do not take ownership of the seas they sail and the areas where they fish, or hunters do not take ownership of the forests where they hunt, should producers or farmers take ownership of the land they farm?

“The time will come when a war waged for the purpose of checking a nation in its abuse of the soil will be regarded as a holy war.” — Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

It has been more than three years since Queen Elizabeth II of England passed away. The year before her death was a difficult one for the Queen. In October 2021, she was seen using a cane regularly for the first time during a service at Westminster Abbey. Between December 2021 and June 2022, her participation in public events was drastically reduced, missing important ceremonies such as Commonwealth Day and the State Opening of Parliament. During the celebrations of her 70 years of reign, the Queen appeared only on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, canceling her attendance at other events because she felt “uncomfortable” standing. This person with reduced mobility was the largest landowner in the world, holding the legal title to 6.7 billion acres, about one-sixth of the planet’s land surface.

Technically, part of this land is symbolic ownership. This ownership is mostly institutional and nominal, covering about 89% of Canadian territory and 23% of Australian territory. Canada and Australia do not pay any rent, tribute, or tax. The current King Charles III has no decision-making power over the management of the land, nor does he benefit from the profits derived from its exploitation.

I mention this example because it is an excellent starting point for validating Proudhon’s arguments. Apart from the moral issues related to the ownership of vast territories in former British colonies, the distortions they cause in the real estate sector, or the tax exemptions enjoyed by the British monarchy, what legitimacy does the owner of a piece of land have, if he does not enjoy it, over someone who holds its possession?

“I’m not concerned with generational wealth, that’s its own curse / Anything you want on this cursed Earth / Probably better off gettin’ it yourself, see what it’s worth” — Billy Woods

One sovereign power exercised in virtually every nation in the world is expropriation. This legal instrument allows the state, for reasons of “public utility” or “social interest,” to take property away from a private individual. Thomas Sowell calls this type of “planning” in political rhetoric suppression. It is an overlay of the collective plan created by third parties on the will and plans of individuals, armed with the power of the state and exempt from the costs or consequences that these collective plans impose on others.

According to the rules described by Proudhon, if property did not exist, the state could never impose its will, since it is not the original occupant, does not work the land, and has no social contract.

With regard to the compensation paid by the state following expropriation, this compensation is appropriate to what the state has acquired and not to the value that the owner has lost. Small business owners have invested not only in the acquisition of the property, but also years of effort in developing reputations and contacts with their clientele. In the case of private properties, the value of the compensation does not cover the sentimental value, the loss of community ties with neighbors, and even the possibility of having to move to communities with more expensive housing or higher rents.

In addition to the inequalities produced by the legal system that protects private property rights, there are also structural adversities inherent in the concept of property that limit human and environmental development.

Nature functions through systemic units, yet property is defined by artificial geographical boundaries. The division of land along these arbitrary lines causes the fragmentation of ecosystems and destroys local biodiversity. These private plots and the management carried out by each owner contribute to the interruption of biological corridors and the disruption of local species habitats.

Water resources are also victims of this type of subdivision. When an owner makes isolated decisions about the surface water that flows on their land, such as implementing physical barriers or diverting its natural course, they ignore the downstream impacts, damaging the ecological continuity necessary for fish and sediment transport. In addition to these impacts, pollution of this type of water resource also affects other owners who benefit from it.

Faced with this scenario of fragmentation and isolated management, overcoming the impasses imposed by the private property model has not only involved legal reform, but also profound technological change. While rigid property rights confined nature to arbitrary plots, progress in productive efficiency began to offer a path to territorial decompression. Through innovation, it has become possible to dissociate human growth from constant geographical expansion, allowing technology to act as a vector for the liberation of areas once subjected to intensive exploitation.

The transition from animal traction to mechanization made it possible to free up and restore vast areas of pasture and cropland previously dedicated exclusively to feeding horses. It is estimated that this development has allowed between 495 and 890 million acres worldwide to be returned to nature or converted to other uses.

At the same time, genetic and biotechnological revolutions have tripled the yield of the land that now feeds the global population. Nitrogen synthesis, precision agriculture, controlled environment cultivation, and process automation have also been fundamental in optimizing the productive efficiency and carrying capacity of agricultural land.

Today, 58% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, which occupy only 1% of habitable land. This process of urbanization is one of the most important factors for human prosperity, not only because it reduces the cost of transporting goods, but also because it facilitates the exchange of knowledge and the division of labor. This demographic density should not be considered, as it often is, a problem of “overpopulation.”

“Looking at what happens over time likewise gives no support to the theory that “overpopulation” causes poverty… Various desperate expediencies have been used to try to salvage the “overpopulation” thesis, beginning in Malthus’ time and continuing to today… thinly populated areas mean much higher costs per person to supply water, electricity, sewage lines, telephone lines, hospitals, and numerous other costly things. Sub-Saharan Africa’s thin population per square mile is one of its many major economic handicaps.” — Thomas Sowell

The arguments against Proudhon’s ideas arise most vehemently from the libertarian political school, specifically from Frédéric Bastiat, through the philosophical current of Natural Law. He argues that property rights are essential for encouraging productivity and innovation. Without the security that private property guarantees to the individual, they are discouraged from saving, investing, or improving their land and their tools of labor. Without property, society can lose the mechanisms that enable the creation of wealth and human progress.

Karl Marx himself saw Proudhon’s theory as utopian! Although he originally praised the work What is Property? as a scientific manifesto of the proletariat, his opinion changed in 1847 with the publication of The Poverty of Philosophy, a satirical response to Proudhon’s book The Philosophy of Poverty.

Marx criticized Proudhon for treating economics through a moral lens. The statement “property is theft” is scientifically empty, since “theft” presupposes the existence of legal property, and is therefore contradictory.

In this sense, the right to private property is not, therefore, an abstract truth because it has never been contested, as Proudhon proposes, but rather a set of historical social relations that change over time and are part of the structural fabric of society.

Cell phones are only harmful to an individual’s health and well-being depending on how they are used. In essence, they are just a tool with various functions, and are not intrinsically evil or benign. The same can be said of property rights. Their value depends on how they are applied and the legal framework that supports them.

In his book The Mystery of Capital, economist Hernando de Soto formulated and popularized the concept of “dead capital.” A native of Peru, the author describes a situation common in former communist or developing countries, where extralegals were forced, by existing legislation or lack thereof, to create a parallel economy. In the year the book was published (2000), De Soto estimated the global value of this dead capital at approximately $9.3 trillion.

If we look at the efforts of an extralegal to build a home, we quickly reject Proudhon’s ideas. In these cases, the individual not only needs to find vacant land, but also to occupy it personally with his family. Next, he needs to erect a tent or shelter with the materials immediately available. Depending on the country, straw mats, mud bricks, cardboard, plywood, corrugated iron sheets, or tin cans are used, ensuring physical possession, since legal possession is not available. Once the basic structure is complete, the family installs furniture and household items. Without access to credit and with the urgent need to build something more durable, residents begin to store materials progressively. After the house is built, which has to be done in stages, and some stability is achieved, the installation of flooring and water, sewage, and electricity networks begins. Only after several years can the owners of the house begin to live in peace.

Private property transforms individuals into responsible and productive people. They no longer need to rely on social relationships with their neighbors or informal local agreements to protect their rights and property. Freed from these constraints, they can convert their physical assets into financial capital, using them as collateral to obtain credit, attract investment, or expand their businesses.

While in former communist or developing countries the challenge lies in correcting a legal flaw, integrating informal social contracts into an official legal system through extralegal reform, in developed countries the challenge is different. In the case of Portugal and other advanced economies, where excessive bureaucracy blocks real estate development, we are not faced with a situation of “dead capital,” but rather with what we might call “ghost capital.” (See article On Property II)

“— Um tipo disse que a propriedade é um roubo. É uma frase estúpida, porque se é um roubo, então a propriedade é legítima, porque só se for legítima o roubo é um roubo. Mas a observação não é minha… o tipo disse isso, porque. Mesmo querendo negar a propriedade, só o soube dizer em termos de proprietário. É o vício mais entranhado no homem…”

“— A guy said that property is theft. It’s a stupid statement, because if it’s theft, then property is legitimate, because theft is only theft if it’s legitimate. But the observation isn’t mine… the guy said that because, even though he wanted to deny property, he could only express it in terms of ownership. It’s the most ingrained vice in man…”

— Vergílio Ferreira