“Not all psychopaths are in prison. Some are in the boardroom”

— R. D. Hare

When I was a child, I remember my father turning on the National Geographic channel on weekends. These programs allowed me to observe a reality I wasn’t used to. Beyond the moments of beauty and landscapes that only nature can produce, these shows displayed the interaction between animals of the same species, as well as interspecific relationships. Despite the occasional violence shown in these programs, I never felt disturbed by those images. Perhaps I was already somewhat desensitized from having a veterinarian father who used to bring live animals home for consumption, or from seeing my grandmother bleed a lamprey and hang it on the clothesline as if she were drying a sock.

However, I am convinced that the real reason the brutality of these images never shocked me is that, since I was a boy, I realized that the laws of nature, though implicit, are well-defined.

Nature and wildlife are anarchic, there are no leaders in nature. There are self-organizing systems, such as the division of labor in ant colonies, the structure of a beehive, or the hierarchy in a wolf pack. Even the lion at the top of the food chain is not immune to diseases, bacteria, other lions, large herbivores, or one of those animals with a rifle in the back of a safari jeep. The rules defining the interaction between these living beings were defined long ago. They were established over hundreds of millions of years. These laws cannot be bypassed, they do not change according to the regime in power, and they do not vary based on the occupied territory, they are immutable.

Criminal law is essentially religious in its origin. In times past, Egyptian priests exercised legal powers. In Ancient Greece, justice was considered an emanation of Zeus, and punishment was seen as divine vengeance. In Rome, the religious origins of criminal law are clearly demonstrated by old traditions, archaic practices that persisted until a late date, and by legal terminology itself. While in primitive societies criminal law was inseparable from religion, the interests served were, ultimately, social. By punishing offenses against the gods, Rome protected the integrity of society itself, evolving from a system of sacred rituals to a structured system of public justice.

Crime (crimen) originally meant accusation, guilt, reproach, or fault. Currently, it is defined as an act or offense that violates the law and is punishable by it. However, since each country defines its own legal system, an act considered a crime in one jurisdiction might not be in another. European Union countries, much like the United States, share certain common principles or laws, however, each nation or american state maintains its own specific legislation.

Among the ancient Germans, only two crimes were punished by death according to Tacitus, treason and desertion. According to Chinese philosophers Confucius and Mencius, impiety is a greater crime than murder. In Egypt, the slightest sacrilege was punished by death. In Rome, the pinnacle of criminality was found in crimen perduellionis (high treason). Just as the brown bear exhibits different behaviors depending on the ecosystem it inhabits, such as varying hibernation patterns, diets, and circadian rhythms, it is natural for humans to adopt rules that adjust to the culture of their region.

However, to what extent does the law discourage criminal behavior? Or is it effective in detecting and identifying criminal acts? And if crime is a social and legal construct, does it even exist?

It is impossible for a person to be genetically prone to crime, since crime is legislative, nor to doing evil, since that evil is a philosophical and moral question. George Washington, one of the founders of the United States and a major proponent of liberty, was a criminal and an enemy of the British Empire. There is, therefore, a fundamental difference between what is legal and what is just or decent, and although both are human constructs, the legal system or the respective authorities cannot always define them.

If there were no laws, would you be more prone to committing crimes? Perhaps I wouldn’t pay the parking meter next time I parked in downtown Porto. Even now, as I sit here writing, no offense comes to mind that I have a great desire to commit. I wouldn’t be capable of, nor do I have the desire to, drive to the supermarket to buy a steak thick enough to hide a deadly pill inside to give to the neighbor’s dog, no matter how much he barks at six in the morning. If that happens, it wasn’t me. I am using the specificity of this declaration to defend my innocence.

“The lawbreaker is thus no longer an evil-minded man or woman, but simply a debtor, a liable person whose human duty is to take responsibility for his or her acts, and to assume the duty of repair”

— Herman Bianchi

Society, in general, has a misguided perspective on crime and criminals. There is a vision that without law and order, crime would be unleashed upon the world. Crime is a cultural or economic issue, nobody would start committing crimes tomorrow just because they became legal.

Regardless of how each country structures its legislative and judicial systems, all crimes fall under the violation of property rights. These include the right to ownership and exclusive control over goods, resources, or assets, whether created or voluntarily exchanged, and self-ownership. This concept, established by John Locke, asserts that every individual holds exclusive jurisdiction and sovereignty over their own body and mind.

If I commit a crime against a person, I engage in an act prone to direct retaliation and the fostering of cycles of violence, whether with the victim or the victim’s family, friends, or neighbors. Ostracization and social exclusion can be consequences, as can the psychological impact that the act would have on me. These repercussions are felt on a smaller scale for crimes against another person’s private property, but they exist nonetheless. The consequences of crime are, therefore, intrinsic to the criminal act itself, without the need for a penal structure.

The 1960s were a time of transition that preceded a period of drastic change in the world and, particularly, in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement, led by figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, and John Lewis, among many others, focused on securing rights already provided for in the Constitution but not applied to all citizens:

- Civil Rights Act of 1964: Officially prohibited segregation in public spaces, education, and employment, ending the Jim Crow laws that prevailed in Southern states;

- Voting Rights Act of 1965: Eliminated barriers to voting, such as literacy tests and poll taxes, which prevented Black citizens from fully participating in democracy;

- Fair Housing Act of 1968: Prohibited discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.

The achievement of these rights did not occur without enormous resistance from the established powers. It was a period that fostered significant institutional violence, with political assassinations of great historical relevance and violent urban riots. This landscape provided the perfect setting for the election of one of the most controversial figures in modern history, who would shape the future of generations to come, not only in the United States, but worldwide.

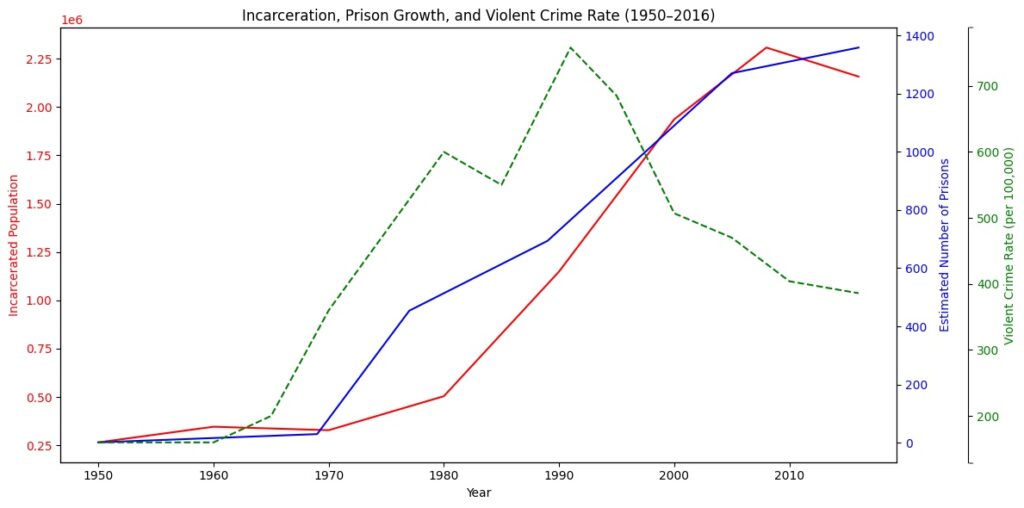

In 1969, Richard Nixon, the 37th President of the United States, initiated a reform of the American prison system in response to the crime wave that began in the 60s. During his term, in addition to modernizing old prison facilities, Nixon built or initiated the construction of 430 new prisons and jails.

At the same time, Nixon created several crime-fighting laws that remain the political foundation for the war on drugs and organized crime today, namely:

- Controlled Substances Act (1970);

- Organized Crime Control Act (1970) – The RICO Act;

- Creation of the DEA – Drug Enforcement Administration (1973).

(Note: To observe the true scale of the impact Nixon had on the global economy, I recommend analyzing the charts at wtfhappenedin1971.com)

In the image above, three aspects can be observed. First, the prison expansion anticipated the increase in detainees, a physical necessity for the system. Second, although crime peaked in the 90s, the reduction in the prison population only occurred shortly before 2010 due to the length of sentences. Finally, external demographics explain the phenomenon: between 1950 and 2010, the American population grew from 150 to 308 million. While the general population doubled in six decades, the number of inmates decupled.

Okay, so it’s not that bad, I thought it would be worse. I was expecting you to say it had tripled or quadrupled. By the way, what did you say? Decuped? What’s that? Deca-what?

Decupled.

That’s it! What does that mean?

It means it grew tenfold.

Free political dissidents from they cages / But leave ’em open / We got lists of names, pages and pages / Wouldn’t want to waste the space the previous regime gave us

— Billy Woods

In the book Are Prisons Obsolete?, the activist Angela Davis calls for the abolition of prisons. In the final chapter, the author presents the alternative, the transition from a punitive model to a restorative model, the redirection of funds from the prison system to social institutions and community programs, and the decriminalization of certain activities, specifically drug use, sex work, and immigrant status.

Severing the idea of justice from prison facilities is something that many people just can’t wrap their heads around.

So you want more criminals and crazy people running loose? Is that it? The ones I catch in traffic every day are enough already. Cutting into my lane without signaling, honking because I took a fraction of a second at a green light, or yelling at me at intersections. Or the ones who appear on the news every day, those fucking politicians creating problems instead of solving them. You want more of those around?

But you know who the worst of them all are? Capitalists, investors, bankers! Those Elon Musks and Jeff Bezoses playing with people’s lives. With the wealth they have, they could end all of society’s ills!

And your bosses? Should they be arrested too?

No, I don’t know if they should be arrested, but my bosses aren’t as rich as those guys.

What about religious institutions? The wealth of the Catholic Church alone would eradicate many ills, yet they continue to ask for more donations with their baskets at the end of mass.

Yeah, that’s not right either. Maybe they could do more, but they already do so much for the disadvantaged.

And the government? You pay taxes, don’t you? Aren’t they there to solve these problems? Why do you pay almost half your salary, and none of the public services work properly?

They often don’t work properly, but no system is perfect!

And the judicial system?

What about it?

Is it a perfect system?

No, of course not. I believe some people have been wrongly convicted, but it’s a very low percentage. Just as I believe some who were released shouldn’t have been. But what are you getting at?

Nowhere, just making conversation.

You’re just trying to make me crazy!

“Do not confuse justice with truth. Justice is done in the name of truth. And truth remains to be found”

— Reb Ares

Herman Bianchi argued that the traditional, vertical, and inquisitorial criminal justice system fails in its goals of rehabilitation and treatment. That “crime”, as defined by the State, often serves to exclude the most vulnerable members of society.

Bianchi proposes the replacement of the current punitive model with a model of responsibility on the part of the offender, and one that is restorative in favor of the victim. Instead of the offense being seen as a crime against the State, Bianchi argues that it is a conflict between individuals, focused on the material and immaterial harm caused to the victim. His model returns responsibility for the actions to the offender and an active role to the victim. The objective is not punishment or retribution, but rather the reparation of harm and reconciliation.

For violent crimes, where direct mediation might not be safe, Bianchi proposed the creation of “sanctuaries”, special spaces or procedures that would protect the public and the victim while allowing for true justice through conflict resolution, instead of traditional punitive incarceration. This refuge does not treat the offender with impunity, it merely replaces the sterile isolation of prison with active responsibility. In his view, these places would function as conflict resolution clinics where the offender is compelled to face the consequences of their actions. The sanctuary allows the legal system to cease being a punitive arm and instead become a mediator.

The current system doesn’t work. The inmate is never rehabilitated since they are isolated from the society to which they will one day return, and the victim ends up paying three times for the harmful act. They pay once at the moment of the act, a second time with the legal costs incurred to obtain justice, and a third time as a taxpayer to maintain a public prison system. And unfortunately, in this last case, criminal or victim, crazy or sane, guilty or innocent, we all pay.